Parallel Shadows: Lessons from Germany’s Collapse for America’s Working Class Today.

From Weimar hyperinflation to America’s Rust Belt, the trauma of economic collapse echoes across time. Richard Wolff’s analysis warns that failing to protect workers and dismantling labor power opens the door to demagogues—and history shows just how dangerous that can become.

The echoes between the economic traumas that struck Germany after World War I and those unsettling the American working class today. Unpacking everything from the hyperinflation that dashed German hopes in the 1920s to the triple threat of automation, offshoring, and immigration in late 20th-century America, the post draws thought-provoking parallels — and missteps — between two superpowers at their breaking points. Expect surprising connections, a few historical detours, and a candid look at whether the lessons of yesterday really reach us today.

Once, in a cramped Berlin flat, a grocer named Marta tucked away her life savings for her children—only to discover, after 1923, that those banknotes might as well have been wallpaper. Her story could have ended in old black-and-white photos, but echoes of that disillusionment still ring today. Think it couldn’t happen in a 21st-century superpower? Consider the American worker watching factories shutter, unions dissolve, and communities fray. Are we just recycling old heartbreaks with new packaging? Let’s wander through the back alleys of economic trauma, from Weimar to the Rust Belt, and see what shadows the past casts on our present.

From Berlin Savings to Rust Belt Losses: Echoes of Economic Trauma

The collapse of the German working class in the early 20th century stands as a stark warning about how quickly economic security can vanish. In the decades leading up to World War I, German workers were among the most educated and optimistic in Europe. They had built up real savings, often across generations, believing that their thrift and hard work would secure their families’ futures. Germany was a rising economic powerhouse, competing with Britain and France on the global stage. But the trauma of economic collapse was just around the corner.

After the war, Germany faced crushing reparations and the loss of its colonies. Yet, it was the hyperinflation in Weimar Germany that delivered the most devastating blow. In 1923, the currency collapsed from about 6 or 7 marks to the US dollar to a staggering 1,000,000,000 marks per dollar. Decades of careful saving disappeared in a matter of months. As one survivor put it,

“You may have saved for 50 years across three generations. And what you had saved was now enough to buy maybe a quarter pound of butter.”

This was not just a financial loss. The trauma of economic collapse shattered faith in the future, destroyed social cohesion, and left scars that would last for generations. Research shows that hyperinflation can obliterate decades of progress and confidence for the working class. The emotional devastation was as real as the economic one—identity, belonging, and hope all vanished alongside the money.

Fast forward to late 20th-century America, and the echoes of this trauma are easy to spot. The American working class, especially in the manufacturing heartlands of the Rust Belt, once enjoyed rising wages and job security. Like their German counterparts, many believed this prosperity would last forever. But the 1970s and 1980s brought a new kind of shock. Automation, offshoring, and waves of plant closures dismantled once-secure livelihoods almost overnight. Well-paid, unionized jobs evaporated, and with them, the sense of purpose and community that had defined entire towns.

The American working class decline was not triggered by war or hyperinflation, but the results were strikingly similar. Decades of progress were reversed in a few short years. The trauma of economic collapse was felt not just in lost income, but in lost identity and shattered dreams. Many families kept reminders of this sudden reversal—a layoff letter tucked away in a drawer, a union card from a closed factory—as grim mementos of how fast things can fall apart. My own grandfather kept his layoff letter for years, a silent reminder of the day stability vanished.

Both the German and American experiences reveal how societies can underestimate the speed at which fortunes change. The collapse of the German working class and the American working class decline are not just stories of lost money—they are stories of lost confidence, belonging, and hope. The lessons from Weimar Germany’s hyperinflation and America’s industrial decline remain painfully relevant today.

The Triple Punch: Technology, Outsourcing, and Migration in America’s Downturn

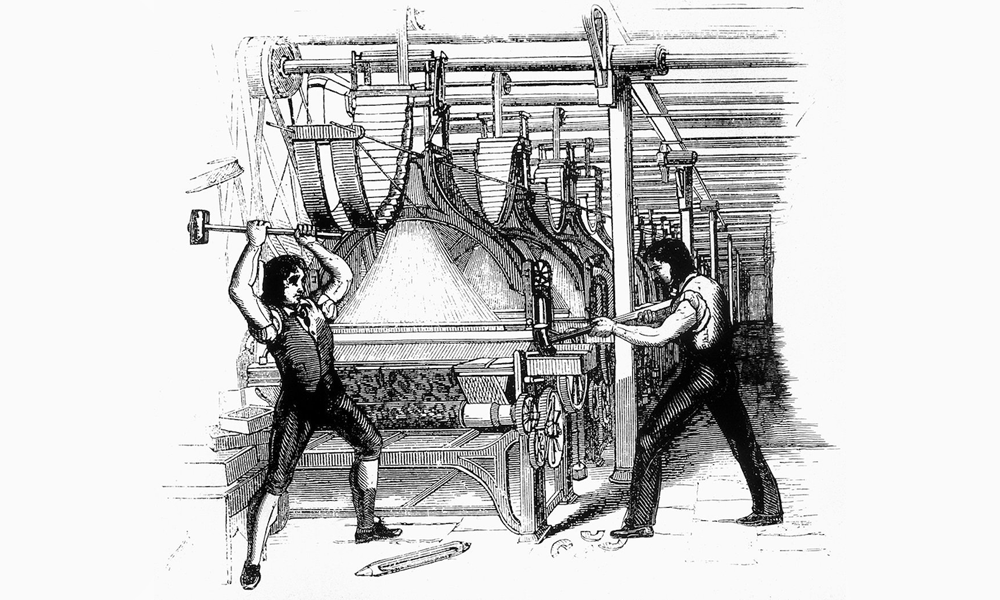

In the 1970s and 1980s, the American working class faced a seismic shift. This era marked the beginning of what many now call the “triple punch”—a rapid succession of automation, outsourcing, and increased migration that would reshape the nation’s economic landscape. These forces did not arrive gently; they hit with the force of a tidal wave, leaving communities and families scrambling to adapt.

First came the technological revolution. Computers, robotics, and early artificial intelligence swept through factories and offices, automating tasks that had once provided stable, well-paid jobs. Research shows that automation and job loss in America were especially devastating for unionized manufacturing workers—often white, male, and the backbone of the country’s industrial might. As machines replaced people, millions of jobs simply vanished.

Next, corporate-driven globalization took hold. Companies, eager to maximize profits, relocated manufacturing and production to countries like China, India, and Brazil, where labor was cheaper and regulations looser. The numbers are stark: during the 1970s and 1980s, millions of American manufacturing jobs were lost to offshoring. This wasn’t just a business decision—it was a social earthquake. Towns that had thrived on factory work saw their economic foundations crumble almost overnight.

The third blow came with increased immigration. Many newcomers arrived seeking opportunity, willing to work for lower wages and under tougher conditions than Americans had grown accustomed to. While research indicates that immigration was not the root cause of economic decline, it became an easy scapegoat for angered workers. Political leaders and media figures, rather than addressing the real drivers of job loss, often pointed fingers at immigrants, fueling division and resentment.

As these changes unfolded, the old security nets—strong unions, stable factory jobs, and a sense of community resilience—dissolved quickly. Workers watched as their livelihoods disappeared, their unions lost power, and their neighborhoods frayed. One haunting question lingered:

“Workers watched factories shutter, unions dissolve, and communities fray. Are we just recycling old heartbreaks with new packaging?”

Mainstream political parties, both Republican and Democrat, often cheered these transformations. They prioritized corporate profits and economic “efficiency” over the needs of working families. The result? Systemic neglect left many Americans unprotected, echoing the trauma experienced by Germany’s working class after World War I—a group that also saw its savings, jobs, and hopes wiped out by forces beyond its control.

A tangential but important question arises: Could “AI-proof jobs” have shielded regions like the Rust Belt from decline, or would corporations have simply found new loopholes to cut costs? The evidence suggests that without strong protections and a commitment to community resilience, even the most “secure” jobs are vulnerable in the face of relentless corporate-driven globalization and technological change.

Scapegoats and Demagogues: How Economic Despair Breeds Extremism

Throughout history, periods of economic collapse have often led to the rise of scapegoating and demagoguery. The parallels between Germany’s collapse in the early 20th century and the recent trajectory of the United States are striking, especially when examining the roots of Trump and white working-class resentment. In both cases, economic hardship created fertile ground for leaders to redirect public anger away from the true causes—such as corporate decisions and government policy—and toward marginalized groups.

In post-World War I Germany, the working class faced a devastating sequence of losses. Once considered among the most modern and prosperous in Europe, German workers saw their savings wiped out by hyperinflation and their livelihoods destroyed by the Great Depression. The trauma was profound: families who had saved for generations suddenly found their wealth reduced to almost nothing. As research shows, such economic despair often breeds a desperate search for answers—and for someone to blame.

Adolf Hitler capitalized on this desperation. He pointed to Jews and foreigners as the culprits behind Germany’s woes, fueling a narrative that redirected frustration away from the real architects of economic collapse. This scapegoating did not solve Germany’s underlying problems, but it did provide a convenient outlet for collective anger. The rise of fascism in Germany is a stark historical parallel to the rise of economic nationalism and resentment in the United States today.

Fast forward to recent decades in America, and a similar pattern emerges. As automation, offshoring, and waves of immigration transformed the labor market, many white working-class Americans—especially those in unionized manufacturing—experienced a sharp decline in job security and wages. Instead of addressing the root causes, such as corporate strategies to maximize profit or the failure of economic policy to protect workers, political leaders often redirected blame toward immigrants and minorities.

This tactic is not new. As studies indicate, scapegoating is a recurring, damaging response to economic uncertainty. Demagogues exploit these moments of social stress, using fear and division to gain power. The rise of ICE and harsh anti-immigrant policies in the US echoes historical repression, drawing uncomfortable comparisons to the special police forces of fascist regimes. As one observer put it:

“It takes an extraordinarily… person with a very ambiguous relationship with the truth to start babbling to get people’s misery to turn them against other people and make them miserable, too.”

The cyclical nature of demagoguery reveals a troubling lesson: when leaders fail to confront the true sources of economic pain, history repeats itself. The historical parallels to fascism are not just academic—they shape contemporary politics and influence the rise of economic nationalism. One can’t help but wonder: if more leaders had addressed the real culprits, would history textbooks be shorter—and less grim?

Ultimately, the weaponization of social stress by political leaders is a pattern that continues to haunt societies facing economic decline. The story of Germany’s collapse and America’s current struggles serves as a warning about the dangers of scapegoating and the persistent allure of demagogues.

Desperation Economics: Fantasy, Decline, and the Power of Denial

Desperation economics in the U.S. is not just a phrase—it’s a lived reality for many Americans, especially as the nation’s economic standing shifts on the global stage. The country’s political and financial elite, often called the “donor class,” seem to cling to the fantasy that America can simply will itself back to its former glory. Despite mounting deficits, a projected $2 trillion shortfall in 2024, and a looming expiration of the 2017 tax reform, this group remains fixated on tax cuts and short-term gains. Their belief in American exceptionalism persists, even as the facts increasingly contradict it.

Recent U.S. policies—like unpredictable tariffs and sudden economic reversals—mirror the kind of panic seen in declining empires. Watching the bond markets react to these moves is like observing a teetering seesaw: each new policy unbalances something else, sending ripples through global markets. This is not the steady hand of a confident superpower, but the frantic gestures of a nation unsure of its future. As one observer put it,

“A declining empire does not have the options that a rising empire does.”

This pattern isn’t new. History shows that when empires face decline, desperation breeds risky, unreliable policy cycles. Germany’s collapse after World War I is a stark example. The German working class, once proud and hopeful, was devastated by war, inflation, and depression. Their savings vanished almost overnight, and their sense of security was shattered. The trauma of sudden decline led to political instability and the rise of dangerous demagogues.

America’s own trajectory since the 1970s echoes this pattern. The rise of economic nationalism, automation, and corporate-driven globalization has gutted well-paid manufacturing jobs. Many of these jobs either disappeared due to technology or were relocated overseas in search of cheaper labor. The result? A working class left behind, while the donor class and big corporations reaped the benefits. Political parties, both Republican and Democrat, have largely failed to address these issues, instead supporting policies that favor profits over people.

Research shows that refusing to recognize decline can actually accelerate it. The U.S. has run persistent trade imbalances and accumulated debt for decades, much like late-stage empires before it. Tax cuts for the wealthy and policy indecisiveness only mask deeper insecurities. The recent downfall of UK Prime Minister Liz Truss, after her risky economic plan spooked bond markets, is a warning sign of what can happen when leaders ignore fiscal realities.

Today, the U.S. faces stiff competition from China, whose projected 2024 growth (5%) outpaces America’s (2.8%), according to the IMF. Yet, instead of adapting, American leaders double down on old strategies—tariffs, tax cuts, and gestures meant to signal strength. These actions may please donors, but they do little to address the underlying issues. The world is watching, and so are the bond markets. The more the U.S. clings to denial, the more unstable its economic future becomes.

History’s Rearview: What Could Break the Cycle?

The story of the American working class decline is not just a tale of lost jobs or stagnant wages. It is a cautionary narrative with deep historical parallels to fascism, echoing the collapse of Germany’s once-powerful labor movements in the early 20th century. In both cases, the systematic dismantling of strong labor organizations left workers fragmented, vulnerable, and easily manipulated by demagogues.

After World War II, the American left—once represented by robust organizations like the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO)—faced relentless attacks. Leaders were arrested, fired, or ostracized. The CIO, which once covered a third of the U.S. workforce, now represents only a tenth. As one observer put it,

“Everything has been done to break those organizations down. And so, we are defenseless against Mr. Trump, aren’t we?”

The result is a workforce that lacks the solidarity and collective power needed to resist divisive rhetoric and policies.

Research shows that a fragmented workforce is more susceptible to manipulation by political opportunists. History demonstrates that when social movements are stifled or divided, societies become fertile ground for demagogues. In Germany, the trauma of war, hyperinflation, and depression shattered the working class, paving the way for Hitler’s rise. In the United States, decades of automation, offshoring, and political neglect have similarly eroded the foundation of labor movements, leaving workers isolated and searching for answers.

Yet, history also offers hope. Sometimes, change begins in unexpected places—a minor strike in an overlooked industry, a spontaneous act of solidarity, or a new coalition that transcends old divisions. These moments remind us that the cycle of decline is not inevitable. But real reform requires more than new policies or political promises. It demands truth-telling about the roots of economic hardship and a commitment to rebuilding broad, inclusive coalitions.

After WWII, the vacuum left by dismantled labor organizations in America amplified vulnerability to authoritarian rhetoric. The lesson is clear: resilience requires solidarity, not scapegoating. When workers are divided—by race, gender, or immigration status—they become easier targets for those who seek to exploit their fears and frustrations. Demagogues thrive in such environments, offering simple answers and convenient scapegoats, while the underlying problems remain unaddressed.

As the U.S. faces new economic and political challenges, the historical parallels to fascism become harder to ignore. The decline of labor movements has not only weakened the American working class but also undermined the country’s ability to resist authoritarian trends. To break the cycle, Americans must look beyond surface-level reforms and confront the deeper issues of power, inequality, and representation in the workplace and beyond.

In the end, the enduring importance of strong labor movements cannot be overstated. They are not just economic institutions—they are bulwarks against division and manipulation. The path forward lies in solidarity, truth, and the courage to build something new from the lessons of the past.

TL;DR: Trauma, whether from inflation or automation, leaves scars. The collapse of Germany’s working class and America’s current struggles share chilling similarities, from political scapegoating to the hollowing-out of hope. If we ignore history, we risk stumbling down the same dark corridors—again.

CollapseOfTheGermanWorkingClass, TraumaOfEconomicCollapse, HyperinflationInWeimarGermany, AmericanWorkingClassDecline, AutomationAndJobLossInAmerica, RiseOfEconomicNationalism, TrumpAndWhiteWorking-classResentment, HistoricalParallelsToFascism, Corporate-drivenGlobalization, DesperationEconomicsInTheU.S.,WeimarGermanyhyperinflation, RustBelteconomictrauma, riseoffascism parallels, automationandlabordecline

#EconomicHistory, #WorkingClassStruggles, #Hyperinflation, #AmericanDecline, #Globalization, #AutomationImpact, #RiseOfNationalism, #HistoryRepeats, #EconomicTrauma, #FascismWarning,#WorkingClassCrisis, #EconomicCollapse, #FascismWarning, #LaborDecline, #HyperinflationParallels, #RustBeltDecline, #Demagoguery, #RichardWolffAnalysis, #AutomationImpact, #HistoricalRepeats